By Jaclyn Carr, BSN & Brianna Giannotte, BSN (with Monica Moore, MSN, RNC)

Many of us don’t realize how well the intricate system of feedback loops in our reproductive endocrine system work until they are disrupted in some way. Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) represents an example of this. It is a disorder characterized by a collection of symptoms, and is prevalent in patients who present at infertility clinics, affecting 5-10% of women at reproductive age. An estimated 90% of anovulatory cases are related to PCOS. In addition to negatively affecting metabolic parameters and ovulation, it is also associated with several mental health issues (such as depression and anxiety) in the women who have it. It is, though, manageable by using medical and non-medical interventions. It is beyond the scope of this article to fully explain PCOS, so in part 1, we will discuss the pathophysiology of PCOS, its diagnostic criteria, insulin and leptin resistance, psychological implications and the clinician’s unique role in supporting the patient with PCOS.

Pathophysiology of PCOS

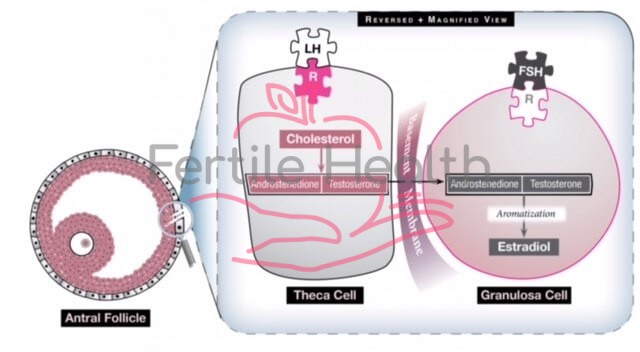

In ovulatory women, under the influence of a properly functioning hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian (HPO) axis, the menstrual cycle is characterized by the growth and development of (usually) a single follicle that is extracted from that month’s cohort (group of follicles). In response to GnRH stimulation, the anterior pituitary gland secretes two important gonadotropins: Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH) and Luteinizing Hormone (LH). FSH acts on the ovary to help grow and mature small follicles. That month’s dominant follicle is one which has acquired the most FSH receptors. This follicle will continue to grow and mature at the expense of the remaining small follicles, which then get reabsorbed by the body (but are still deducted from the woman’s total egg supply). Growth of the dominant follicle generates estradiol production and elevated estrogen levels signal FSH production to cease via a negative feedback system, but a high and sustained estrogen level will trigger a one-time surge of LH which causes ovulation to occur.

In a woman with PCOS the HPO axis does not express normal functionality. The pulsatile hormone GnRH is altered, resulting in increased LH activity by the pituitary gland. This increase in LH increases theca cell stimulation (see Fig 1), which produces androstenedione and testosterone, two androgens, and the resulting hyperandrogenic milieu of the ovary precludes normal follicular growth, maturation and ovulation. The ovary, then, becomes comprised of many small, antral follicles that never become dominant. The collection of these follicles can cause an increase in the size of the ovaries and generate a slightly elevated basal serum estrogen level. It remains unknown why PCOS occurs and whom it affects, but it is thought that genetics and environmental factors have a complex interplay in its emergence and clinical manifestations.

Diagnostic Criteria

PCOS is not defined or diagnosed by one simple symptom and is often a diagnosis of exclusion for women who have oligo-ovulation and evidence of hyperandrogenism (such as acne alopecia and hirsutism (male-pattern hair growth and texture) once other disorders are excluded. It affects women of all shapes, sizes, and backgrounds. Although symptoms can start at menarche, most clinicians are reluctant to diagnose a relatively newly menstruating adolescent with PCOS as menstrual cycle irregularity is normal in the first year post menarche and can resolve in time. The diagnostic criteria most commonly used today were revised in an international expert workshop in Rotterdam, The Netherlands, in 2003 and are called The Rotterdam Criteria where the following were established: PCOS can only be diagnosed when a patient has at least two out of three features: oligo/anovulation, hyperandrogenism (biochemical or clinical), and the appearance of polycystic ovaries upon ultrasound. Hyperandrogenism is diagnosed either clinically (by the clinician observing androgenic symptoms) or biochemically (such as elevated serum free testosterone levels).

These criteria were revised in 2018 by an international committee which made a few changes. First, due to the availability of sensitive transvaginal ultrasound machines, polycystic ovarian morphology (PCOM) is characterized by the presence of 20 or more follicles (<10 mm) in either ovary or a ovarian volume ≥ 10 ml on either ovary as seen by transvaginal ultrasound, often situated around the periphery of the ovary (or ovaries). The 2018 guidelines also state that if a woman has irregular menstrual cycles and hyperandrogenism that the ultrasound is not necessary for diagnosis, although many clinicians still prefer to perform this. Anti-Mullerian Hormone (AMH) levels are often elevated in PCOS patients, although this is not specific to PCOS as elevated levels can be found in women without the condition. In PCOS–affected women, an elevated AMH level is reflective of a higher number of follicles arrested in the pre-antral and antral stages that fail to ovulate.

Other conditions that can cause irregular menstrual cycles (pregnancy, hypo– and hyperthyroidism, ovarian failure and hyperprolactinemia) and hyperandrogenism (congenital adrenal hyperplasia, adrenal tumor and androgen–secreting tumor) must be ruled out first, so in addition to serum bHCG levels, basal FSH and LH levels, thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), prolactin, total and free testosterone, 17 hydroxyprogesterone (17OHP), dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS) are drawn. One of the most difficult differential diagnoses is discerning a woman with functional hypothalamic amenorrhea (FHA) versus a lean woman with PCOS. Classically women with FHA have a low BMI, but it also can be in the low/normal range. Both conditions are characterized by anovulation and ovaries which appear to have many small follicles in a resting state. While hyperandrogenism is not a component of FHA, women with the condition may have hirsutism due to their ethnicity, further confusing the clinical picture. One way to distinguish FHA from PCOS is with blood testing and ultrasound examination. Women with FHA often have low to normal basal FSH and LH levels (due to hypo–stimulation of the ovaries) and a low estrogen level whereas women with PCOS typically have elevated serum LH levels and low to normal FSH levels. On ultrasound, the uterus and ovaries of women with FHA are small or small/normal, whereas women with PCOS typically have an increased ovarian volume (>10 ml). There is emerging research on a possible connection between both FHA and PCOS as not all women present with characteristic features of either condition and FHA and PCOS do have some overlapping characteristics.

Insulin Resistance and Leptin Resistance

Although the diagnosis of insulin resistance (IR) is not part of the Rotterdam Criteria, it is incredibly prevalent in women with PCOS. An elevated BMI increases the chance that a woman with PCOS has IR, but even non-obese women with PCOS are far more likely than their size-matched counterparts without PCOS to develop insulin resistance. In addition to the health consequences of IR (such as metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes mellitus), it also exacerbates and contributes to hyperandrogenism in a patient population who is already suffering from it.

The gold standard for diagnosing insulin resistance is to use a hyperinsulinemic euglycemic clamp, a test which must be performed in a hospital setting. To most, this is unreasonable, so indirect testing for IR is done. In women with PCOS in a preconception clinical setting, the suggestion is to do perform an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) given the high risk of women with PCOS to develop impaired glucose tolerance and gestational diabetes in pregnancy. Although somewhat time-consuming, this test is preferred over fasting plasma glucose and insulin levels alone as it can diagnose impaired glucose tolerance at an earlier stage. In women with PCOS who are not in a high-risk category (i.e., BMI<25 kg/m2, not trying to conceive, no personal or family history of impaired glucose tolerance) obtaining at least baseline fasting glucose, insulin and hemoglobin A1c levels can be helpful in order to get a ‘snapshot’ of that patient’s glycemic status.

….the conditions of overweight and obesity are common in women with PCOS and weight loss can feel impossible since intuitive eating is not effective when hunger and satiety cues are unreliable.

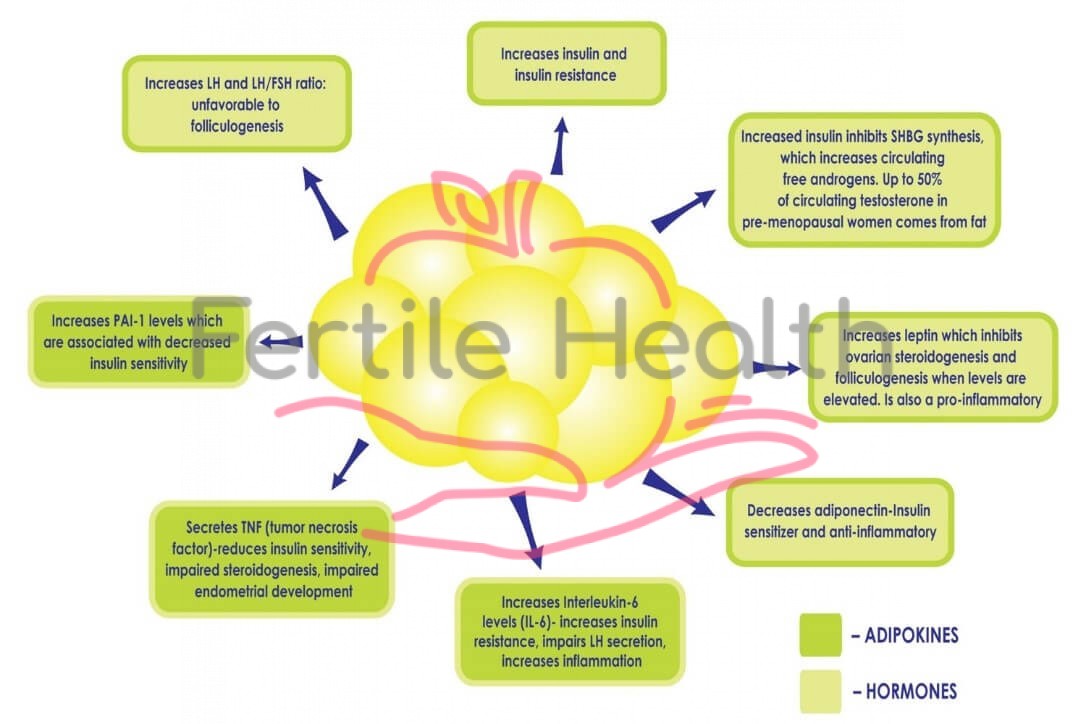

When a woman has PCOS, being overweight or obese intensifies the metabolic consequences. White fat cells are metabolically active. At a normal level, they are protective as they provide a safe home for lipids and keep fat out of organs. When there are too many fat cells, they can get overloaded and burst, releasing fatty acids into the bloodstream which can affect every organ. These fat cells get ‘stuck’ between the cells in organs and cause them to be stiff, damaged, less functional and cause chronic inflammation. It is not uncommon to diagnose ‘fatty liver’ in a woman with PCOS who is obese, as the liver is particularly vulnerable. In addition, an excess in adiposity can perpetuate existing hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance by disrupting the delicate balance of cytokines and hormones produced by adipose tissue (see Figure 2), for example, decreasing the production of cytokines which increase insulin sensitivity, and increasing those which promote inflammation and insulin resistance. Excess insulin further contributes to abdominal adiposity and hyperandrogenism creating a vicious cycle in PCOS patients that can be difficult to overcome.

In addition to insulin resistance, patients with PCOS and obesity may also suffer from, what some term, leptin resistance. Some studies have shown that leptin levels are higher in obese PCOS patients compared to lean patients. Leptin is a protein produced by adipose tissue which regulates the body’s energy balance and appetite. When properly functioning, an increase in leptin signals the brain to reduce a person’s appetite and a decrease in leptin does the opposite, it signals the brain to increase appetite to provide the fuel needed for energy. In many PCOS patients with obesity, however, this system is faulty and, despite increased leptin concentrations secondary to the increase in adipose tissue, the efficacy of leptin decreases, leading to leptin resistance. Leptin resistance is considered an important risk factor for the pathogenesis of overweight and obesity, as the body remains insensitive to elevated levels and signals to the woman that she is still hungry/not satiated even after eating. Many women with PCOS complain of ‘never feeling full’ due to this resistance and continue to eat, leading to an increase in adipose tissue, which results in increased leptin resistance and perpetuates this damaging cycle. As a result, the conditions of overweight and obesity are common in women with PCOS and weight loss can feel impossible since intuitive eating is not effective when hunger and satiety cues are unreliable.

Education about the significance of having PCOS is vital and the main focus should be addressing the patient’s perceived needs while decreasing the long-term risk factors.

Figure 3: Disruption of the HPO axis in a PCOS patient. There is excess LH stimulation on the theca cell resultaing in an increase in testosterone levels, an androgenic ovarian environment, and anovulation (resulting in low progesterone levels). Increased leptin levels due to an excess of adipose cells affect GnRH secretion. Elevated insulin levels contribute to hyperandrogenism.

Impaired leptin secretion not only affects body weight but can have a detrimental effect on ovulation (see Fig 3) and even fertilization in normal-weight PCOS patients. It alters the release of GnRH from the hypothalamus, decreasing anterior pituitary stimulation (and therefore FSH and LH secretion), and preventing the development of a mature oocyte. In addition, the granulosa cells also store and produce leptin, and high levels of leptin decrease their aromatization capacity which ultimately interferes with the ability of a dominant follicle to produce adequate amounts of estrogen (see Fig 1). A small, observational study found a direct correlation between the concentration of leptin found in the follicular fluid (FF-leptin) (which has been correlated with fertilization rate) in lean women with PCOS who have underwent IVF when compared to normally ovulating, weight-matched women.

Managing PCOS

PCOS is not curable but is manageable with proper diagnosis and the patient’s understanding of (and dedication to) the life-long strategies that can ameliorate its consequences. Education about the significance of having PCOS is vital and the main focus should be addressing the patient’s perceived needs while decreasing the long-term risk factors. Potential metabolic sequelae and dangerous comorbidities associated with a PCOS diagnosis include dyslipidemia, impaired glucose tolerance, visceral obesity and being susceptible to the development of diabetes and cardiovascular disease (CVD). Some research suggests that the PCOS condition, particularly when accompanied by obesity, is associated with chronic inflammation and oxidative stress which are hallmarks of cancer development. In fact, women with PCOS have an increased risk (2-6 fold) of endometrial cancer. There is also research suggesting that women with PCOS have higher incidences of autoimmune thyroid disease even in the absence of thyroid dysfunction symptoms. Women with PCOS may require more specific screening for this disease or screening at a younger age given their PCOS diagnosis. While the syndrome is nondiscriminatory, there is ethnic variation in the presentation and intensity of symptoms. For example, East Asian women appear less clinically affected by hirsutism and have a lower BMI than Caucasian women. Hispanic women incur a higher prevalence of metabolic syndrome and hypertriglyceridemia than other ethnic groups, and increased central adiposity, IR, diabetes and metabolic risks are found in South East Asians and Indigenous Australians.

One of the important goals of PCOS management is increasing the body’s sensitivity to insulin. Hyperinsulinemia, in addition to leading to insulin resistance, is a powerful contributor to excessive stimulation of ovarian androgens, and also inhibits sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG, a glycoprotein that helps to bind to androgens and reduces free testosterone levels which can improve hyperandrogenic symptoms). Lifestyle interventions are considered the first-line treatment for PCOS patients. Although weight loss is preferable when a patient with PCOS is overweight or obese, some suggest that the clinician emphasizes strategies that improve health as opposed to the focus solely being on weight loss. For example, exercise is the strongest insulin sensitizing strategy and is still helpful even in the absence of weight loss. Conversely, many PCOS patients are advised to lose weight prior to conceiving and they can do so in unhealthy and unsustainable ways, such as eating a no carb or extremely low-calorie diet, which might result in weight loss but can actually worsen metabolic parameters and is associated with high rates of recidivism.

Patients’ attitudes toward exercise can vary greatly and it is difficult for those living with obesity to engage in exercise or physical activity. They may feel physically unable, emotionally uncomfortable and/or apprehensive about being publicly embarrassed.

Patients’ attitudes toward exercise can vary greatly and it is difficult for those living with obesity to engage in exercise or physical activity. They may feel physically unable, emotionally uncomfortable and/or apprehensive about being publicly humiliated. Some patients in higher BMI categories might be embarrassed or reluctant to go to a gym or a group exercise class where they perceive that everyone is thinner or fitter than them and, until recently, it was difficult for plus-size patients to find attractive workout clothes. For this patient population, it might be helpful to encourage them start exercising with the use of home videos, find a trainer who is experienced in dealing with body-diverse clients, or find a body-positivity mentor in person or online. Beginners can work towards simple, non-scale-centric goals such as increasing their workout time from 30 to 45 minutes or being able to walk a mile, instead of relying on weight loss as the only outcome.

In addition to increasing insulin sensitivity, decreasing abdominal adiposity has shown to be a successful treatment for both the hormonal and metabolic characteristics of PCOS and might restore ovulation and menstrual cycle regularity in some patients. Achieving “metabolic fitness” such as making improvements in lipid and glycemic status is also a reasonable goal. Adolescent women with PCOS, who are surrounded by images of thin, fit girls both in person, on social media, and in mainstream media on a regular basis, can find it difficult to make the mental shift from attempting to replicate a too-thin, unachievable body shape to feeling healthier and achieving a reasonable weight that is sustainable. There is no single diet that works for all clients with PCOS. Ideally, women with PCOS should meet with a nutritionist who has an endocrinology background and can create individual meal plans for based on food preferences, availability, budget and other important factors. Proper nutrition counseling is a cornerstone in the treatment plans for PCOS patients.

The Psychological Consequences of PCOS

Although it is paramount to decrease or delay the onset of the long-term risks associated with PCOS, the patient’s focus might be on reducing or tempering its physical and emotional consequences. Unequivocally, PCOS can affect a woman’s appearance which can negatively impact her self-esteem, particularly in adolescence. First, there is a high correlation between women with PCOS and elevated BMI. A reported 40-80% of women in this population are overweight or obese, often storing excess fat in the abdominal area. This form of adiposity called ‘visceral fat’ has a reciprocal relationship with hyperinsulinemia, where it is both exacerbated by, and contributes to, excess insulin.

The androgenic manifestations of PCOS can also be devastating. Women with the condition often present with hirsutism, moderate to severe acne and/or alopecia that is difficult to combat. Starting OCPs or other medications to reduce serum androgens will limit the progression of these and may help control acne, but they will not reduce the amount of current body hair, and scalp hair regrowth can be a long process. Since many women utilize electrolysis or laser hair removal (when they can afford to) to reduce the appearance of hirsutism, during the physical exam clinicians should ask about any hair removal methods in order to determine the extent of clinician hyperandrogenism. The use of the Ferriman Gallwey score (a visual scale that assesses hirsutism) can be helpful for documenting their baseline score (a score ≥ 4-6 indicates hirsutism depending on ethnicity), then noting any improvement subsequent to interventions. Excess androgens can also result in acne which can persist into the adult years. Consulting a dermatologist for acne and skin changes can help improve appearance.

This collection of symptoms can cause many PCOS patients to state that they do not “feel feminine” and, over time, often lead to depression or low self-esteem ultimately impacting their quality of life. Patients diagnosed with PCOS report increased psychological disturbances, and lower sexual satisfaction. Elevated BMI and hirsutism were the two highest reported features that contributed to decreased psychological well–being, while biochemical, endocrine and metabolic issues seem to be less urgent, an important distinction for counseling patients.

It is vital that the nurse recognizes the unique consequences of women with PCOS when working with this particularly vulnerable population. Many of these women have been victims of weight bias or prejudice, even in health care settings. They might feel imprisoned in a body that even they don’t understand, potentially mortified by their appearance at a pivotal time in their lives, and the brunt of jokes by classmates, officemates, even teachers and health care providers. Weight bias is pervasive, and people feel justified mocking those in higher BMI categories because they perceive that being overweight or obese is a choice and, therefore, under their control. So although women are taught that ‘lifestyle changes’ can make a difference and ‘losing a small amount of weight is helpful’, this task seems daunting when their body craves foods that are caloric and fatty, and they do not achieve a feeling of fullness when they should. Weight bias has been shown to be incredibly detrimental to weight-diverse patients, and those who are victims of it feel frustrated and powerless leading to binge eating and less exercise, the opposite of the desired outcome. In order to reduce bias, it would benefit the clinician to educate themselves on the complex reasons that people overeat prior to educating their PCOS patients.

Involve and empower the patient by asking her to identify her own goals, such as being able to run a race, feel comfortable in a group class with others…etc. During the medical history, clinicians can ask a question such as “What are some things you feel unable to do now that you would like to do” and then collaborate with her to make changes to accomplish these. Identifying short-term, achievable, concrete goals can embolden and encourage the patient and take the focus off weight loss, which has probably been attempted many times in the past. In fact, exercise is the greatest insulin-sensitizing strategy, regardless of weight loss.

To some, the diagnosis of PCOS is a relief as they now have justification for their androgenic symptoms and unexplained weight gain. For others, it is met with anger and resentment as it upends their version of adolescence or womanhood that they have probably had since childhood.

To some, the diagnosis of PCOS is a relief as they now have justification for their androgenic symptoms and unexplained weight gain. For others, it is met with anger and resentment as it upends their version of adolescence or womanhood that they have probably had since childhood. They are acutely aware that their bodies are different than those of their classmates and feel that they are not as attractive to potential partners. Control of their glucose levels and weight might feel chaotic, resulting in a body that is as mystifying to them as it can be to others. Clinicians must realize that acceptance of PCOS as a life-long disease can take years.

PCOS is a complex, multi-layered condition that is heterogenous in both its manifestations and its presentation. The physiology of these patients is distinct in that they have barriers to the protective feedback systems that maintain balance in the body, such as leptin and insulin, resulting in weight gain and hyperinsulinemia. Management of these patients is centered around sensitizing them to insulin, preferably utilizing non-pharmacological methods first. Having PCOS can create an emotional toll on a woman which must be considered by those who care for them, and education and interaction should be undertaken without bias or blame. The future of PCOS lies in researching the genetic and epigenetic etiologies of the disorder in order to refine the diagnosis and hopefully discover a cure. Patients should also be made aware of pharmacologic treatment strategies, and potential future reproductive options (which will be discussed in Part 2).

* The authors would like to thank Neil Chappell, MD for his help reviewing and editing this manuscript.