Everyone would agree that functionality of the uterine lining is incredibly important for implantation of the blastocyst to take place. The question of how to measure this, termed ‘uterine receptivity’, has been studied extensively in the literature. The methods that have been used in the past were indirect, assumptive and not reproducible. Researchers in Spain have created a new tool which has been shown to be promising for identifying molecular markers for uterine receptivity.

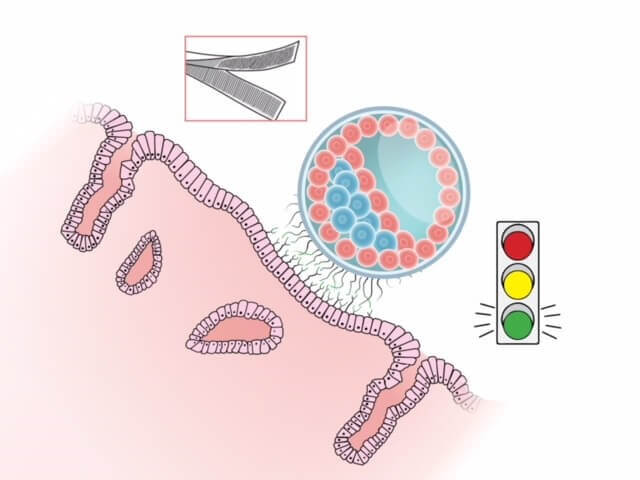

Remarkably, as the blastocyst floats within the uterine cavity looking for a place to land, a dialog takes place between the blastocyst and the endometrium. In order for a successful implantation to take place, the blastocyst needs to be at the appropriate stage, and it needs to signal the uterine lining to ‘accept’ it. Within the uterine cavity, once ready for implantation, the microvilli present on the trophoblast cells of the blastocyst act as one side of ‘velcro’ to adhere it to the uterine lining. The embryo is in search of a receptive endometrium (the other half of the velcro) which will ‘fasten it’ to the uterine wall. The hormonal preparation of the uterus plays a critical role each month in creating this environment in which the blastocyst can adhere to the endometrium in the hope that implantation will take place.

The uterine lining undergoes changes during the two phases of the menstrual cycle that prepare it for blastocyst implantation. During the proliferative phase, it grows due to the increasing production of estrogen by the ovaries. The second phase is called the secretory phase where the production of progesterone, produced by the corpus luteum, converts the endometrial lining to a secretory one, changing the cells to prepare for implantation (a process called decidualization). Should implantation not take place, the hormone levels will fall, resulting in a shedding of the lining, which results in menses. Studying the mid-secretory phase is of great importance since the window of implantation (WOI) takes place then. The sweet spot of WOI is approximately a 2-day period when the uterus is prepared to accept the implantation of a blastocyst. Conventionally, it was assumed that every woman had the same WIO, (approximately 8-10 days after ovulation) so embryo transfers would be scheduled to take place during this time. This theory has recently been challenged, with researchers proposing that the WOI can vary among women.

Research has been done extensively to detect and determine criteria necessary in order to call an endometrium ‘receptive’. In the past, this was done using histological criteria, i.e. the microscope appearance of the endometrium (termed the Noyes Criteria). Certain days of the menstrual cycle have typical microscopic characteristics and a pathologist would determine if the sample looked like day 16 or 17..etc (dates were reported with ovulation normalized to day 14-so an endometrium that was day 17 by Noyes Criteria should be 2 days post ovulation). As one can imagine, there is much variability and subjectivity in this interpretation between pathologists, plus womens’ cycles can show considerable variability. Also, just because the cells have the appearance of a typical cycle day 16, for example, doesn’t mean that the lining is actually receptive. That would just be implied. As a result of these limitations, and some recent studies that found this morphological dating method to have poor predictive value, this method of assessing uterine receptivity is no longer widely used.

One can also look at the appearance of the lining by ultrasound in the late proliferative phase. Many studies have focused on the endometrial thickness and type (triple-line vs homogenous appearance). Although the lower limit of an acceptable lining has not been agreed-upon by researchers or practitioners (most would arguably be satisfied with a lining of 7 mm or above) that information is a reflection of the adequacy of the proliferative phase, which tells us that the lining was properly primed by estrogen, but doesn’t give us any information other than that. Ultrasound in the secretary phase is not helpful, as it shows a thick, homogenous lining that doesn’t usually affect clinical decision-making, so is not routinely performed.

Over the last decade, different ways of studying the endometrial lining more directly have been investigated, first by attempting to identify the substances that were generated at the time of implantation, the cytokines, adhesion molecules and other proteins. To date, this line of investigation has been unsuccessful, so the focus has shifted to the stage that leads to the production of these substances, the stage of RNA transcription. Transcriptomics allows the study of gene expression by looking at the mRNA produced. It can provide a molecular profile of the status of the endometrium by telling us what genes are actually “turned on”. Gene expression profiling is now widely used for other disciplines, such as tumor classification.

With the relatively recent advent of DNA microarray analysis we can measure the expression of thousands of genes simultaneously, allowing us to explore which ones are expressed in the mid-secretory phase, when implantation takes place. The discovery of this technology was a major turning-point in the study of endometrial receptivity and several studies were undertaken to determine which of these genes were important during the WOI. Researchers agree that there is a specific and unique action that takes place during the process of transcription, when RNA creates the ‘script’ for a protein, in order for the endometrium to become receptive, but the identification of the specific genes involved was elusive until recently. A group in Spain identified 238 genes related to endometrial receptivity and collected the data to create a tool, named the endometrial receptivity array or ERA (Diaz-Gimeno, et al 2011). This test purports to identify if an endometrium is receptive or not based on the mRNA profile or the endometrial gene expression. It further differentiates the non-receptive category into pre- or post-receptive) in natural or hormone-replacement (HRT) cycles, regardless of it’s appearance by ultrasound or under the microscope (histological). This group then applied their tool by testing it on patients with recurrent implantation failure (RIF) by performing a multi-center, prospective study. What they found is that the WOI was ‘displaced’ in 26% of the women with RIF, so in 1 out of 4 patients with RIF, dysynchrony between the blastocyst and the endometrium might be to blame (Ruiz-Alonso, et al, 2013). They then did a second ERA test on the patients who had the displaced WOI to confirm that by adjusting the progesterone start or transfer day (see more on this below) increased implantation rates. They performed a subsequent adjusted embryo transfer (termed a personal embryo transfer or pET) and demonstrated a 50% pregnancy rate and a 38% implantation rate in this group of patients (which is the rate similar to the control group who did not fail a treatment cycle). This data supports the concept that the conventional window of implantation differs among women (at least a fourth of us) maybe only slightly in some cases, but enough to preclude implantation.

The test is performed in the secretory phase of either a natural cycle or a hormone replacement (HRT) cycle. If during a natural cycle, then the biopsy is done on LH surge + 7 . If during an HRT cycle, then the biopsy is performed on exogenous progesterone start + 5 (120 hours post start of progesterone). The biopsy sample is sent to the lab and analyzed (this takes approximately 2 weeks) and results are termed either ‘receptive’ or ‘non-receptive’. If non-receptive, it further analyzes the sample as pre-receptive or post-receptive. If pre-receptive, then the patient needs more time (hours or days) of progesterone, so the progesterone is started earlier or the transfer is moved later. If post-receptive, then the WOI has already passed, so the recommendation would be to start the progesterone later or move the transfer earlier. The recommendation is to repeat the cycle after modifying it according to the suggested intervention (more or less days of P) and the biopsy is redone to confirm that the endometrial tissues sent now receptive. This step is center-specific with some practices often performing a repeat mock cycle with biopsy and others only occasionally repeating it, but still using the recommended progesterone modifications for the frozen embryo transfer cycle, thereby creating the patient’s personalized embryo transfer(called pET). For more information on the specifics of the results and testing criteria, see the video here.

Although the data collected so far is promising, there are some limitations in the study design that should be considered when interpreting results. One is that all of the studies performed so far have relatively small sample sizes. Another is that there was no effort (in most studies) to separate out the embryo quality so that this important variable could be controlled. (There is a recent, retrospective study, in Japan where the researchers only transferred back euploid embryos with optimistic results, but it was retrospective and had a small sample size.) Furthermore, in the initial ERA studies, the non-receptive group was not further stratified to include a segment who did not have pET prior to their next transfer, so it is not known if they would have been pregnant just due to trying again, without further intervention. Finally, keep in mind that if 25% of RIF patients had a displaced WOI, 75% did not, implying that there are other factors (embryo quality among them) that could be the cause of implantation failure.

The importance of determining the timing of endometrial receptivity has always been emphasized in reproductive endocrinology. Now, instead of just relying on the way the endometrium appears, either by ultrasound or microscopically, some researchers suggest that we have the added benefit of being able to study the molecular changes that happen within the endometrium and act on these results to form a personalized prescription for subsequent transfers. Although exciting, further studies are needed to confirm this small subset of studies and also to determine if this test will be useful for an expanded group of women (Currently it has been suggested that it should be offered to those who have failed >2 IVF cycles or >1 donor oocytes cycle.) Methods of non-invasive testing are also being explored and might be a viable option within the next decade. The idea that every woman has their own personalized window of implantation (and that we can determine and take advantage of this) is a new and exciting concept in REI.

Special thanks to Paul Bergh, MD, FACOG For his assistance with editing this article.