Ovarian Reserve Testing and Diagnosing Diminished Ovarian Reserve

Dayna Browning, BSN, Jennifer Dwyer, BSN and Monica Moore, MSN, RNC

Edited by Paul Bergh, MD

A woman’s ovarian reserve refers to both the quantity and quality of her eggs, and diminished ovarian reserve means either or both of these factors are declining.

Ovarian reserve testing specific for the quantity of available oocytes consists of biochemical and ultrasonographic tests that represent a snapshot of where a woman falls along this continuum.

Surprisingly, women have the most eggs (oocytes) when they can least use them, prior to birth as a 20 week fetus! After birth, this oocyte pool dwindles until very few remain at the time of menopause. Ovarian reserve testing specific for the quantity of available oocytes consists of biochemical and ultrasonographic tests that represent a snapshot of where a woman falls along this continuum. It’s critical to have an accurate assessment of reproductive potential when planning for pregnancy, whether utilizing advanced reproductive technologies (ART) or not. When proceeding with ART, ovarian reserve testing dictates stimulation protocols to avoid unwanted outcomes, like cycle cancellation or ovarian hyperstimulation. Nurses are often the ones who interpret and review these results with patients, so in this article, we will explore the available tests, their applicability and pitfalls, and how best to discuss with the outcome with patients.

Regarding the quality of oocytes, the millions of eggs that represent a woman’s oocyte pool are dormant for years, arrested in meiosis (cell division for sex cells). The next time these oocytes are re-activated and meiosis resumes is after selection within the dominant follicle, at the time of ovulation with the luteinizing hormone (LH) surge. So, at the time the oocytes are expected to resume cell division, they may have been paused in the middle of cell division from 13 years to as many as 40+ years. Cell division is a process that requires a significant amount of energy. As eggs age, so do does the cell machinery that is crucial for efficient cell division. Accordingly, aging oocytes may not respond as well as younger eggs once recruited from the original supply. These older oocytes are less effective at correctly completing meiotic cell division and thus are at an increased risk for aneuploidy (an abnormal number of chromosomes in the embryo, which is often lethal).This is often the cause for the exponential decline in fertility and increase in miscarriage rates seen in women who attempt to conceive in their later reproductive years. This decline in the oocyte’s ability to complete meiosis error-free is a reflection of oocyte “quality” and, other than a women’s age, there is no way to evaluate the chance of oocyte meiotic error.

Regarding quantity, the rate of follicular depletion varies considerably among women. Chronological age is an important factor when counseling infertility patients, but it’s important to note that two age-matched women can have very different levels of ovarian reserve. Although some lifestyle choices, such as smoking, trauma from surgery, or radiation/chemotherapy can be detrimental to oocytes, exercise and a healthy diet are important, but not necessarily protective. The fact that a fit, active woman in her 40’s can still have diminished ovarian reserve demonstrates the inescapable reality of ovarian aging.

The fact that a fit, active woman in her 40’s can still have diminished ovarian reserve demonstrates the inescapable reality of ovarian aging.

Diminished ovarian reserve (DOR) is a term used to denote that the decrease in the oocyte pool has reached a level in which it impairs fertility. DOR occurs even in women with regular menstrual cycles. Those who are diagnosed with DOR can be counseled that they will have a lower response to stimulating medications, a higher cancellation rate, and a lower chance of pregnancy after an IVF cycle than an age-matched woman whose ovarian reserve testing is normal.

Although it would be helpful if ovarian reserve testing reflected both the quality and quantity of the oocytes that remain (and are available for that particular patient), there is a stronger association between the outcome of the tests and the quantity of oocytes available, not their quality or competence. Research on the predictive value of the existing tests is mostly undertaken in the setting of a high-risk population, i.e. those who present to infertility centers, and caution should be taken when extrapolating these results to a low-risk group, such as women who have not been diagnosed as subfertile. The applicability of the results, then, should mostly guide clinicians about expected outcomes during ART cycles, for example, response to stimulating medications, possible cycle cancellation, and the chance for pregnancy after a treatment cycle. They are less reliable when used to predict the probability of a natural pregnancy or when menopause will occur. Also, no single test is predictive of reproductive potential and the patient’s medical history and clinical picture should always be considered when interpreting results.

Historically, a follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) level on cycle day 2-4 was used as the ‘gold standard’ of ovarian reserve testing. FSH is produced by the pituitary gland and is an important hormone necessary for follicle growth, particularly small follicles. As a follicle grows, it produces estradiol (E2) and inhibin B, and the increase in these hormones decreases the release of FSH from the pituitary. So adequate early follicular levels of E2 and inhibin B maintain FSH at normal levels. E2 and FSH levels are inversely proportional, so lower E2 levels would signal the pituitary to increase the production of FSH. As a result, it is important to also draw an E2 level when an FSH is drawn to assure that E2 is not elevated (>60-80 pg/ml) which would falsely lower FSH. As women age, the quantity and quality of the follicles that they produce declines. A poor-quality follicle (or a reduction in the number of follicles) results in an E2/inhibin B levels not high enough to provide negative feedback to the pituitary to reduce the production of FSH, so it is over-secreted. Consequently, elevated FSH levels on day 2-4 can be an indicator of diminished ovarian reserve. An FSH level >10 mIU/ml, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) 2nd international standards, is considered a sign of decreased ovarian reserve. FSH alone, though, seems to be a limited measure of ovarian response. It’s specificity and sensitivity vary in the literature, and it’s a poor predictor for pregnancy and live birth, particularly for young (<35 y/o) patients. As a result, most clinicians do not rely on this level alone when counseling patients.

A dynamic measure of ovarian reserve, that has been used in the past but is no longer widely used, is a clomiphene citrate challenge test (CCCT). Women undergoing this test have an E2 and FSH level drawn on day 2-4 of their menstrual cycle. Then, 100 mg of clomiphene citrate is taken orally on days 5-9, and an FSH level drawn on day 10. This has been termed a ‘stress test’ for the ovaries as it might show how ovaries respond to stimulation and reveal more subtle DOR that may be concealed by using a static test/single level. This test is in effect a bioassay of the inhibin B response of the follicle. Clomiphene citrate blocks estrogen’s negative feedback to the pituitary and the hypothalamus, however inhibin B produced by the follicles is not blocked by clomiphene citrate and is still recognized by the brain. In a normal CCCT test, with a sufficient inhibin B response, the FSH with the day 10 blood work should still be suppressed to the normal levels expected on day 3. Recently, though, other methods are increasingly used over this test as some feel that there is only a minimal to moderate benefit over testing FSH levels alone (if any) and is not necessarily cost-effective. As a result, some centers opt to use this test for patients in whom they suspect a poor response to stimulation (over the age of 35, I.e.) whereas others do not use this test at all.

Anti-Mullerian Hormone (AMH) is starting to emerge as the preferred measure of the quantity component of ovarian reserve. AMH is a hormone secreted by the granulosa cells that surround the early, small (up to 4 mm) follicles in the ovary. Normal levels are lab-specific, but many use >1.0 ng/ml as the cut-off. AMH expression is not gonadotropic-dependent, so can be drawn at any time during the menstrual cycle. Levels peak at 25 years of age and decrease with age (the opposite of FSH), with a level <1.0 mg/ml indicating diminished ovarian reserve and very low levels can be seen about 5 years prior to menopause. Elevated AMH levels also have clinical utility, as they would suggest a robust ovarian response, and have been shown to correlate with an increased risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS). AMH can be helpful in predicting the response to gonadotropin stimulation, and possibly pregnancy rates. The data is mixed regarding the predictive value of AMH levels and live birth, although there is some evidence that it might be better than FSH levels in this regard. Also, in women without a history of infertility, a prospective, randomized study found that low AMH levels do not predict a decrease in fecundity as compared to those with normal levels. AMH might also be useful in assessing the need for fertility preservation strategies. The data on AMH as being a reliable predictor of natural fertility is mixed, though, larger studies are needed to elucidate this.

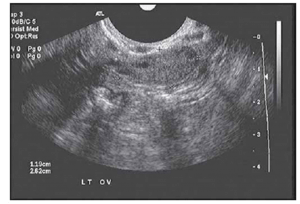

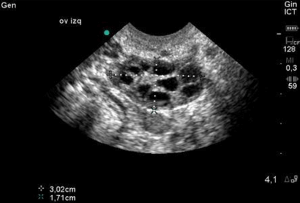

As stated above, the follicles which become dominant and ovulate are just the ‘tip of the iceberg’ and demonstrate the immense attrition rate seen with normal human aging. Only 0.1% of oocytes present at birth make it to ovulation. Every month, a small portion of follicles (containing oocytes) are drawn from a woman’s egg supply in the hopes of being selected to become a dominant follicle. Around day 5-7 of a 28 day cycle, the follicle which has the most FSH receptors becomes dominant and the remaining follicles get reabsorbed by the body. Measuring the number of small (2-10 mm), antral follicles that are present by ultrasound on day 2-4, then, before dominant follicle formation, termed the Antral Follicle Count (AFC) is a helpful measure of ovarian reserve as it can be appreciated that the lower the overall egg supply, the lower the number of follicles available to be recruited. These are the follicles that contribute to the AMH level so it is no surprise that the AFC is highly correlated with AMH levels. This is supported in the literature as women with a lower AFC are more likely to have cancellation for poor response in IVF cycles. The literature is mixed regarding with the lower limits for AFC are, there is some agreement that less than a BAFC of <3-6 is concerning.

Although not well-established until the last decade, AMH and AFC seem to be emerging as the best approaches to procreative testing, as they are the most accurate in predicting poor response to IVF (better than FSH). They are also better at predicting hyper-response and elevated levels of either should alert the clinician to the possibility of OHSS. Although AMH seems to be superior to FSH in predicting live birth, data is conflicting regarding its ability to predict miscarriage rates.

Treatment of DOR

Very few treatment options are available when a woman has been diagnosed with diminished ovarian reserve. One reasonable, and affordable, strategy is advising the patient to begin supplements such as DHEA (Dehydroepiandrosterone) and Coenzyme Q10. DHEA is in a class of steroid hormones known as androgens which are at peak levels in humans in their mid-20s. Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) is an antioxidant that your body produces naturally to use for growth and maintenance and plays a key role in mitochondrial function. There has been recent data that suggests DHEA improves ovarian function, increases pregnancy chances and, by reducing aneuploidy, lowers miscarriage rates. Similarly there is also data that Coenzyme Q10 can not only help preserve the ovarian follicle pool, but also facilitates ovulation of gametes able to support normal development. Other suggestions include maintaining a healthy lifestyle and avoiding factors that can impair fertility such as an elevated BMI and smoking.

Historically, it was thought that superovulating patients with diminished ovarian reserve gave them the best chance of pregnancy during a treatment cycle, but a growing body of research suggests that ‘mini’ or ‘mild IVF’ might offer outcomes similar to conventional IVF cycles. Conventional IVF consists of the administration of high-dose external hormonal injections with the goal of developing a large quantity of oocytes. These oocytes are retrieved during a surgical procedure and later fertilized with sperm in a controlled laboratory setting. In mild ovarian stimulation, or mini IVF, an oral ovulation induction agent such as clomiphene citrate or letrozole is initially used, followed by the administration of low-dose injections to stimulate follicular growth. Because this approach leads to less oocytes retrieved, it can be done with local anesthesia as opposed to general anesthesia. The cost is also less because less injections are used. When comparing conventional IVF and mini IVF, a study found that there is fair to good evidence that clinical pregnancy rates are not substantially different between two types of stimulation in women predicted to be poor responders.

Counseling the Patient

When couples begin their fertility journey they are seeking answers as to why they are unable to conceive or have been experiencing recurrent pregnancy losses. A comprehensive diagnostic workup is the first step to treatment and, for many women, it is found that they have diminished ovarian reserve. Receiving and accepting this message, and its ramifications, is incredibly difficult for patients. As REI nurses it is our responsibility to assist in counseling the patient on appropriate care measures based on their results. Although it is more common to see a decline in ovarian reserve in women over the age of 35, this unfortunately can affect women of all reproductive ages. If a woman’s ovarian reserve testing (hormone levels, follicle count) falls within a normal range, a less invasive option such as IUI (Intrauterine Insemination) may be recommended as first line treatment. However, if a woman is shown to have signs of diminished ovarian reserve (low AMH, high FSH, low AFC) she would need to be counseled on the importance of aggressive fertility treatment such as IVF to optimize her chance of success for a current and potential future pregnancy, the higher chance of cycle cancellation, and the lower chance of pregnancy when compared to women her age with normal ovarian reserve. It is important to share with the patient that as she gets older her reserve and egg quality/quantity will continue to decline. This is especially pertinent for women who want to have multiple children, so ovarian reserve testing results should be taken into context with the couple’s family-planning goals, such as how many children would they ideally like to have.

One of the most difficult and emotionally-charged treatment options to discuss with a patient is the potential need for OD or ED (Oocyte or Embryo donation), as it requires that she accepts the inability to use her own eggs and agree to use someone else’s, a huge shift in her family-building perspective and the loss of a life-long dream.

One of the most difficult and emotionally-charged treatment options to discuss with a patient is the potential need for OD or ED (Oocyte or Embryo donation), as it requires that she accepts the inability to use her own eggs and agree to use someone else’s, a huge shift in her family-building perspective and the loss of a life-long dream. When delivering this sensitive news to the patient or couple it is important to be forthcoming , but empathetic and sensitive as well (Review How to Deliver Bad News here). Realize that the patient needs to essentially grieve the loss of her fertility. When making this phone call, make sure there is adequate time to discuss results and answer any follow-up questions the she (or her partner) may have. So be prepared that this call might take more time and allow for that when planning your day. Setting realistic expectations for the patient in terms of recommendations for treatment and the potential for success is crucial. Keep in the mind that the patient may not readily accept your news and may have an understandably defensive or aggressive reaction. Reminding the patient that you are available as a form of support will allow them to express their feelings and concerns once they are ready. Offering additional support resources for the patient such as speaking with a social worker, or scheduling a follow up appointment with their physician can be offered as well.

Ovarian reserve testing provides important information regarding likely reproductive outcomes in infertility populations. AMH and AFC are emerging as the more widely used tests to evaluate the quantity of oocytes remaining. Evaluating the quality of the remaining oocyte pool remains elusive though is often correlated with age. Currently there is no real treatment for women with DOR, but supplements and personalized stimulation protocols are options. When ovarian reserve testing results are abnormal, nurses need to realize that this news can be devastating to a patient. As a result, time and care should be taken when making the phone call to deliver these results, considering the patient’s clinical situation and desire for family-building.